The UCSF-John Muir Health Jean and Ken Hofmann Cancer Center at the Behring Pavilion is now open. LEARN MORE >

Up to 1.5 million people in the United States suffer from aortic stenosis (AS), a progressive disease that affects the aortic valve in their hearts. Approximately 250,000 of these patients suffer from severe symptomatic AS, often developing debilitating symptoms that can restrict normal day-to-day activities, such as walking short distances or climbing stairs. These patients can often benefit from surgery to replace their ailing valve, but only approximately two-thirds of them undergo the procedure each year. Many patients are not treated because they are deemed inoperable for surgery, have not received a definitive diagnosis, or because they delay or decline the procedure for a variety of reasons.

Patients who do not receive an aortic valve replacement (AVR) have no effective, long-term treatment option to prevent or delay their disease progression. Without it, severe symptomatic AS is life-threatening – studies indicate that 50 percent of patients will not survive more than an average of two years after the onset of symptoms.

Overview of the Disease

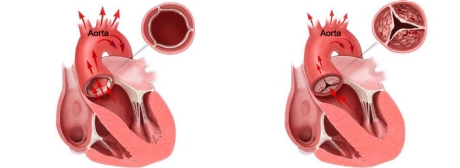

A healthy aortic heart valve allows oxygen-rich blood from the lungs to flow from the left ventricle of the heart to the aorta, where it then flows to the brain and the rest of the body. Severe AS causes narrowing or obstruction of the aortic valve and is most often due to accumulations of calcium deposits on the valve’s leaflets (flaps of tissue that open and close to regulate the flow of blood in one direction through the valve). The resulting stenosis impairs the valve’s ability to open and close properly. When the leaflets don’t fully open, the heart must work harder to push blood through the calcified aortic valve. Eventually, the heart’s muscles weaken, increasing the patient’s risk of heart failure.

Fig. 1 depicts the leaflets of a healthy aortic heart valve which open wide to allow oxygen-rich blood to flow unobstructed in one direction. The blood flows through the valve into the aorta where it then flows out to the rest of the body.

Fig. 2 depicts the leaflets of a stenotic or calcified aortic valve unable to open wide, obstructing blood flow from the left ventricle into the aorta. The narrowed valve allows less blood to flow through and as a result, less oxygen-rich blood is pumped out to the body, which may cause symptoms like severe shortness of breath.

AS is typically a disease of the elderly, as a buildup of calcium on heart valve leaflets occurs as one gets older. It most typically occurs in patients older than 75 years of age. In a minority of cases, a congenital heart defect, rheumatic fever, radiation therapy, medication or inflammation of the membrane of the heart can also cause the valve to narrow.

Symptoms

Patients with severe AS may experience debilitating symptoms, such as:

- Severe shortness of breath leading to gasping – even at rest

- Chest pain or tightness

- Fainting

- Extreme fatigue

- Lightheadedness/dizziness

- Difficulty exercising

- Rapid or irregular heartbeat

Diagnosis

Identification of severe AS can be confirmed by examining the heart and listening for a heart murmur, which is typical of the disease. This can be performed by using imaging tests such as an echocardiogram or electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG), chest x-ray or ultrasound. Receiving an appropriate diagnosis and getting treated quickly is critical, as once patients begin exhibiting symptoms, the disease progresses rapidly and can be life-threatening.

Treatment

Open-chest surgical AVR is the gold standard and an effective treatment of severe AS and has been proven to provide symptomatic relief and long-term survival in adults. During the procedure, the damaged “native” heart valve is removed and replaced with a prosthetic valve. Open-chest surgery is recommended for virtually all adult aortic stenosis patients who do not have other serious medical conditions. For patients who have been deemed inoperable or high risk for traditional open-chest surgery, a procedure called transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is available as a treatment option.

The Edwards SAPIEN Transcatheter Heart Valve is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a therapy for patients with severe symptomatic native aortic valve stenosis who have been determined by a by a heart team that includes an experienced cardiac surgeon and cardiologist to be inoperable or high risk for open-chest surgery to replace their diseased aortic heart valve. Patients who are candidates for this procedure must not have other co-existing conditions that would prevent them from experiencing the expected benefit from fixing their aortic stenosis.

This procedure enables the placement of a balloon-expandable heart valve into the body with a tube-based delivery system (catheter). The valve is designed to replace a patient’s diseased native aortic valve without traditional open-chest surgery and while the heart continues to beat – avoiding the need to stop the patient’s heart and connect them to a heart-lung machine which temporarily takes over the function of the heart and the patient’s breathing during surgery (cardiopulmonary bypass).

For both inoperable and high-risk patients, the valve is approved to be delivered with the RetroFlex 3 Delivery System through an artery accessed through an incision in the leg (transfemoral procedure). For high-risk patients who do not have appropriate access through their leg artery, the valve is approved to be delivered with the Ascendra Delivery System via an incision between the ribs and then through the bottom end of the heart called the apex (transapical procedure).

As with most therapies, there are risks associated with the procedure. TAVR is a significant procedure involving general anesthesia, and placement of the Edwards SAPIEN valve is associated with specific contraindications as well as serious adverse effects, including risks of death, stroke, damage to the artery used for insertion of the valve, major bleeding, and other life-threatening and serious events. In addition, the longevity of the valve’s function is not yet known.

References

- Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(23):2187-98.

- Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(17):1597-1607.

- Bach D, Radeva J, Birnbaum H, et al. Prevalence, Referral Patterns, Testing, and Surgery in Aortic Valve Disease: Leaving Women and Elderly Patients Behind. J Heart Valve Disease. 2007:362-9.

- Nkomo V, Gardin M, Sktelton T, et al. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study (part 2). Lancet: 2006:1005-11.

- Iivanainen A, Lindroos M, Tilvis R, et al. Natural History of Aortic Valve Stenosis of Varying Severity in the Elderly. Am J Cardiol. 1996:97-101.

- Aronow W, Ahn C, Kronzon I. Comparison of Echocardiographic Abnormalities in African-American, Hispanic, and White Men and Women Aged >60 Years. Am J Cardiol. 2001:1131-3.

CAUTION: Federal (United States) law restricts the Edwards SAPIEN transcatheter heart valve to sale by or on the order of a physician. This device has been approved by the FDA for specific indications for use. See instructions for use for full prescribing information, including indications, contraindications, warnings, precautions and adverse events.